- Home

- Education

- Art History and Criticism

- Frida Kahlo and Duality

The period between 1934 and 1940 was tumultuous for Frida Kahlo. Although her husband, Diego Rivera, had been unfaithful in the past, an affair with her sister Cristina was too much for her to bear. During this period she separated from twice and then divorced Rivera at his request. In addition, her various health problems continued to plague her; she required several operations at this time, including an abortion.

The Broken Column, 1944

My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936

It was during this time that Frida began a series of paintings which delved into the roots of her selfdom. As she was a mestiza, she was having something of an identity crisis, along with the rest of post-revolutionary Mexico. Her personal experience was completely analogous with the restlessness and confusion of her beloved homeland. Most of the population was a mix of Spanish and the indigenous peoples to some degree. (Frida's husband even had a claim to a title in Spain which he sold to a cousin for funds to continue his painting in Europe.)

Most of the "mixing" had occurred several generations before, but Frida had the problem of being a first generation mestiza with of the identity problems inherent in a mixed heritage. Her father was a German Jew and her mother was an indigenous Mexican/Spanish mix. After the revolution, Mexico tried to reassert its pre-Conquest sense of self for a new, nationalistic cultural identity with Pre-Columbian society as its model. All things Eurocentric were reviled. Frida as "the patriot," therefore, had the task of trying to reconcile her Mexican self with her European self in her search for wholeness.

This tendency was first explored in My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) which she executed in 1936. In this painting, she illustrates busts of her Mexican maternal and German paternal grandparents connected to her parents via a blood-like red ribbon which she (as a naked child) holds at the center of the composition. Her mother and father are in their wedding garb whose formality is undercut by the anatomically-correct fetus superimposed on her mother's portrait. A sperm cell fertilizing an egg furthers this idea of fertility and reproduction. Frida stands stoically in the middle courtyard of Casa Azul, the house in which she was born (and later died). Her home lies poised between the exotic landscape of Mexico and the sea, implying her family's European ties. In this painting, Frida does not yet seem to be questioning her origins so much as showing herself as the culmination of them. Still, the delicate balance between her two worlds is inherent.

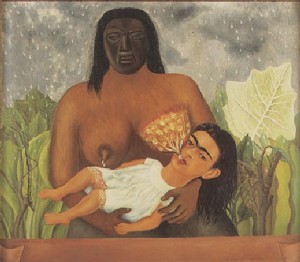

My Wet Nurse and I, 1937

Her next candidate for the series is My Wet Nurse and I (1937). The dichotomy between her Mexican and European selves is apparent. She had always felt that weakness stemmed from her German blood. In this painting, a wet nurse with an Aztec mask nurses an infant Frida in European garb with an adult head. The landscape is lush with vegetation and the sky is raining milk upon them. Milk drips from both breasts as well (a recurrent theme of hers); the breast she is nursing from has vegetation superimposed on it, emphasizing both fertility and nourishment.

This image is fascinating for many reasons. The composition is in many ways traditional, evoking icons of the Madonna and Child. In this vein, even the adult head is not odd as medieval art often showed "Man-child" images of Christ with his Mother. Yet the traditional religious imagery is at odds with the blatant pagan aspect of the Earth as mother. Some believe the nurse is a metaphor for Frida herself, with the indigenous side of her personality lending strength and sustenance to her weaker, European self. Others feel it may be a reference to her Mexican mother. This ambiguity cropped up earlier when she painted My Birth around the time of her mother's last illness and death. Regardless of the various biographical readings, the schism between her selves was becoming more obvious in her work.

The Two Fridas, 1939

The apex of the series is The Two Fridas (1939). After returning home from an exhibit of her work in Paris, she divorced Rivera. This painting illustrating a literal split between her two selves is from this period of turmoil and self-doubt. The composition is striking. On the right is the Mexican Frida in traditional tehuana dress. On the left is European Frida in a colonial white dress, possibly intended to be wedding garb (it is similar in many ways to her mother's wedding dress in "Family Tree"). The two women are seated on a green bench, holding hands. The anatomy of their hearts is superimposed on them both; the one belonging to the European self is seen through a hole in her dress at the breast. A blood line originates at a cameo of Diego as a child held by the Frida on the right. It twines between them both and is ultimately terminated by a medical implement held by the Frida on the left. Blood stains intermingle with the red flowers at the hem of the dress.

This is the painting for which she is best known. Certainly, it is one of the largest (27" x 27") which makes it all the more notable. Also, it is one of the few self-portraits she has done in which she is seen in full. The serene clouds and placid look on the two faces is juxtaposed with the graphic medical imagery to illustrate her internal conflict. The composition is so balanced that the hem of the tehuana skirt is our only cue that she is feeling vulnerabilities which she has come to symbolize with her European incarnation. The efforts of the Mexican self to nurture the second frida have been thwarted by the weaker half.

It is interesting to note that Diego loved and encouraged Frida to dress in the native style that was in en vogue at this time. In fact, Kahlo kept up the style long after it had gone out of fashion to make it uniquely her own. Yet Frida associated her indigenous self with Rivera. Hence, after their initial split, she abandoned her traditional garb and cut her hair as an act of rebellion.

After their reconciliation and remarriage in 1940, Frida again took to wearing her native costumes. It would seem that her internal war, on this matter at least, had been won, if only temporarily. Continued self-portraits in native dress coupled with Mexican landscapes and still lifes strongly support this.

Tree of Hope, Stay Stong, 1946

It is only when her health seriously begins to decline again in 1946 that the topic of duality is broached again with Tree of Hope, Stay Strong. Kahlo reintroduces dual depictions of herself. Her European self is lying on a gurney, her bloody back towards the viewer. On the right is her indigenous self, long identified as her inner source of strength, dressed in a red tehuana dress. She is holding an ex-voto style banner with the title in one hand and a metal corset not unlike the one worn in The Broken Column (of two years earlier) in the other. The idea of duality is further heightened by the differentiation between day and night to divide the composition in half. In the background is the metaphoric barren Mexican landscape which is a hallmark of much of her more surrealistic work.

It is not odd that the splintering of self occurs again in this period. Although her life with Rivera had become more stable in their second marriage, her health had taken a downward swing from which she never fully recovered. All of her self-portraits at this time emphasize her pain. Kahlo was having problems with chronic recurrent depression, alcohol abuse, and addiction to many of her prescription pain killers. Much of her painting was done in a specially made easel so she could paint while confined to her bed. Rivera was spending much of his time away to work on his own art, so she was alone for much of this ordeal. Hence, much of her self-doubt and insecurities were resurfacing in her art.

Although Kahlo's work is intensely autobiographical on the surface, it can be seen as her own patriotic metaphor. Her work was able to transcend the personal to have political and national relevance. Frida held her self up, both in her art and her life, as the ideal post-Revolutionary Mexican. She was politically active right up until her death in 1954. In her home, she surrounded herself with an ever-growing collection Pre-Columbian folk art and indigenous crafts. Frida wrote her own role as the proto-typical Mexican and she played it meticulously. Kahlo meant for her art as well as her life to serve as the example that her "split-personality syndrome" homeland so desperately needed. In exploring and attempting to heal her own schism between worlds with her paintings, she helped Mexico to heal its own.

References

- lecture notes, Modern Mexican Painting, University of Pittsburgh 1996

- Herrera, Hayden. Frida Kahlo: The PaintingsHarperCollins Publishers, Inc. New York 1991

- Rivera, Diego. My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (with Gladys March)Dover Publications, Inc. New York 1991

- Schrimer's Visual Library. Frida Kahlo: Masterpieces W. W. Norton, Munich 1994

this article was originally presented in 1996 at the University of Pittsburgh without the accompanying pictures. All work shown by Frida Kahlo--ed.